HMLTD: West of Eden

About West of Eden by vocalist Henry Spychalski:

Between the oldest and newest songs on this album, there is an age gap of about two and a half years. A few of the songs were written at a time when a HMLTD album was just a distant thought on a blurry horizon, while certain songs were written to tie it all together. Somewhere in the middle of this period, reflecting on our output up until that point, I got the first real idea of exactly what our album would be about. I think that is the moment West of Eden, as a collection, was conceived. What followed was a process of revisiting material and figuring out what fitted into this narrative, and then writing more to expand on and build it all into a singular thing. Dozens of songs were thrown to the wayside. What remains, whilst sonically eclectic, remains because it fits into what we feel is a unified, conceptual whole: West of Eden.

First of all, about the title West of Eden. In Genesis, Cain murders his brother Abel out of envy, as he was the Lord’s favourite. In vengeful Old Testament fashion, the Lord then places a mark on Cain that would prevent anyone from killing him, whilst banishing him in Nod, just East of Eden (the promised land). John Steinbeck’s 1952 novel ‘East of Eden’ channels biblical references to juxtapose both Eden and Cain’s banishment in Nod with the American frontier; a promised land, that is simultaneously marked & cursed. ‘West of Eden’ is a play on and homage to both of these worlds. The cursed place is no longer the East of Eden, but the West. A superpower masked by the façade of luxury and equality, in reality is a dying corpse stained by its own sins against humanity. And like every great empire before it, the West will also eventually consume itself, and in its dying breath clearly position itself not as Eden, but a stones throw away from it; enough for it to be no longer the promised land, but its direct opposite. The possibility of redemption, the proverbial Eden, is to the east and just slightly out of reach. Whether Cain can return to Eden, whether the West can save itself, is a speculative question; whether it ought to is a moral one.

The social, cultural and political backdrop that provides the setting for this album is a bleak one, the West is dying in complacent affluence. Sex is commodified. Faith is dead. Morality is used as a tool, and moulded to fit whatever function is required of it by those who yield it. Western civilization has entered its decadent stage. The era of The Last Man (Letzter Mensch) has come. And all the while, the earth grows sick. Ecological catastrophe is guaranteed.

The West is Dead opens the album and aims to set this scene. Its opening line, ‘Three years ago I said The West is dying right underneath my nose’ is a direct nod to our first release Stained and its manifesto; a polemic on the hypocrisy of Western moral dogmas, as personified through the bloodlust lunacy of US foreign policy. Things have only gotten worse since then. The West is dead. Sick dolphins lap at the tide of shipping tankers, their fins falling off and reddening the wake. The insects have all dropped from the skies, and now clog our swimming pools. The global economy enters free fall; CEOs hang themselves by their neckties.

So that sets the scene: a dying, decadent West. Atomised, alienated and apathetic. This is not intended as a dystopia, but as offering a mirror up to hegemonic late capitalism; where we are and where we’re headed. The album, however, operates on two levels: the macroscopic and the microscopic, and these two arenas play with each other mimetically throughout. The story of the dying West is largely played out through the experience of a specific narrator; Cain. ‘I am the West and the West is dead.’ The story of the album is told through the voice of Cain, who is essentially a personification of the West. He is an analogy of decline, while also its product.

Most of the album involves his odyssey through this Gomorrah. Everyday life in this economy is punctuated by a continuous exchange of humiliations and aggressions. The more man is a social being, the more he is an object. The individual’s journey through this world is one of struggle against this violence. This struggle manifests in various ways, sometimes as a search for morality, as in Satan, Luella & I; sometimes for love, as in Mikey’s Song; sometimes as a battle against loneliness in the city, as in Why? It is a search and a struggle for meaning; meaning as a means of survival. Here, struggle is itself meaning. Ultimately however, the struggle of the individual is that of the West and its squirming only tightens the noose. Like in the Bible, Cain is fated to violence and bloodshed, and violence informs a lot of this album’s subject matter.

The Death Drive (Thanatos) is the overriding logic here, both of the individual and his society, and in Death Drive, I am obviously indebted to JG Ballard in using the car crash as the literal and obvious real-life manifestation of the death drive, at a societal and individual level. The search for meaning West of Eden is doomed to failure, and the return to primordial violence is inevitable. Western society today is marked by violence, and this is explored in various guises throughout the album: in Loaded, as mass shootings; in 149 as domestic violence; in Joanna and its sister track Where’s Joanna, as toxic male repression of femininity, and its externalised counterpart, the actual violent oppression of women in society. Then of course there is Death Drive and its microcosmic counterpart, Nobody Stays in Love. If The West is Dead is a eulogy for the West, Death Drive is its suicide note. The dream of 72 celestial virgins associated with Jihadi suicide bombers is indistinguishable from the lusty greed of the toxic male American dream; they exhibit the same suicidal logic. War is Looming is the obvious endpoint of this logic, and envisions an all-out nuclear war where man finally pushes the big red button and destroys himself; the truest mass suicide possible. He is incapable of doing anything else. ‘When I looked inside myself, I found the dream of a lifeless glass desert. And all of this is lovingly graspable.’ But it’s ok, we were already dead to begin with, and the album starts on this premise. The actual destruction of everything frees us from the pain of struggling against it all. ‘The world is ending. But it’s fine cause all we ever want and ever were is lost in time.’ The end of struggle.

Throughout this introduction, I have been talking in terms of ‘he’ and ‘his.’ All of the above is inextricable from masculinity. Human civilization is patriarchal civilization, and the logic of patriarchy is self-destruction. Much of the album explores this toxic, violent version of masculinity. The album is rife with male insecurity, violence and repression. The corollary of the oppression of women under patriarchy is the repression of the feminine within the male. This is explored in Joanna and Where’s Joanna, which aims at drawing a parallel between oppression and repression and suggesting that these two things spring from the same well and are two manifestations of the same awful phenomenon. The structure of Where’s Joanna should be further explained here. The song is a story about deconstruction and dismemberment, of a female character, Joanna; who we learn from the song’s explanatory prelude, Joanna, is truly meant originally as the feminine within man. A song detailing the gory horrors of dismemberment, the song is itself a patchwork of dismembered parts, reassembled. It is constructed as a series of mondegreens; misheard lyrics from other songs, where through that dismemberment, their meaning becomes grotesque and distorted. While I obviously had to fill in some gaps, the song contains eleven mondegreens, sewn together like Frankenstein’s monster in order, to recreate a mutant whole. The individual cannot be broken down and de-compartmentalised; the individual cannot kill parts of himself off. It is a commentary on how toxic male repression is inseparable from toxic male oppression and violence.

Through a mixture of subversion and mimesis, our unending aim is to critique this monolithic masculinity, be it through hyperbolising and parodying masculinity in its most extreme form, as in our videos, or through acting out machismo bravado and its twin, vulnerability, in our live shows. Whether the alternative vision that we propose and identify with then falls under a queer umbrella or not is debatable, the meaning of queerness being so in flux, though I don’t think it should nor needs to. Politically and socially, it is clearly allied. But ultimately, we identify as men. And that is largely what this album is about: man. What we don’t identify with, is the toxic, monolithic form of masculinity that we have grown up with, that surrounds and polices every corner of our lives. This album is largely about that monolith, and the rife violence which it roots.

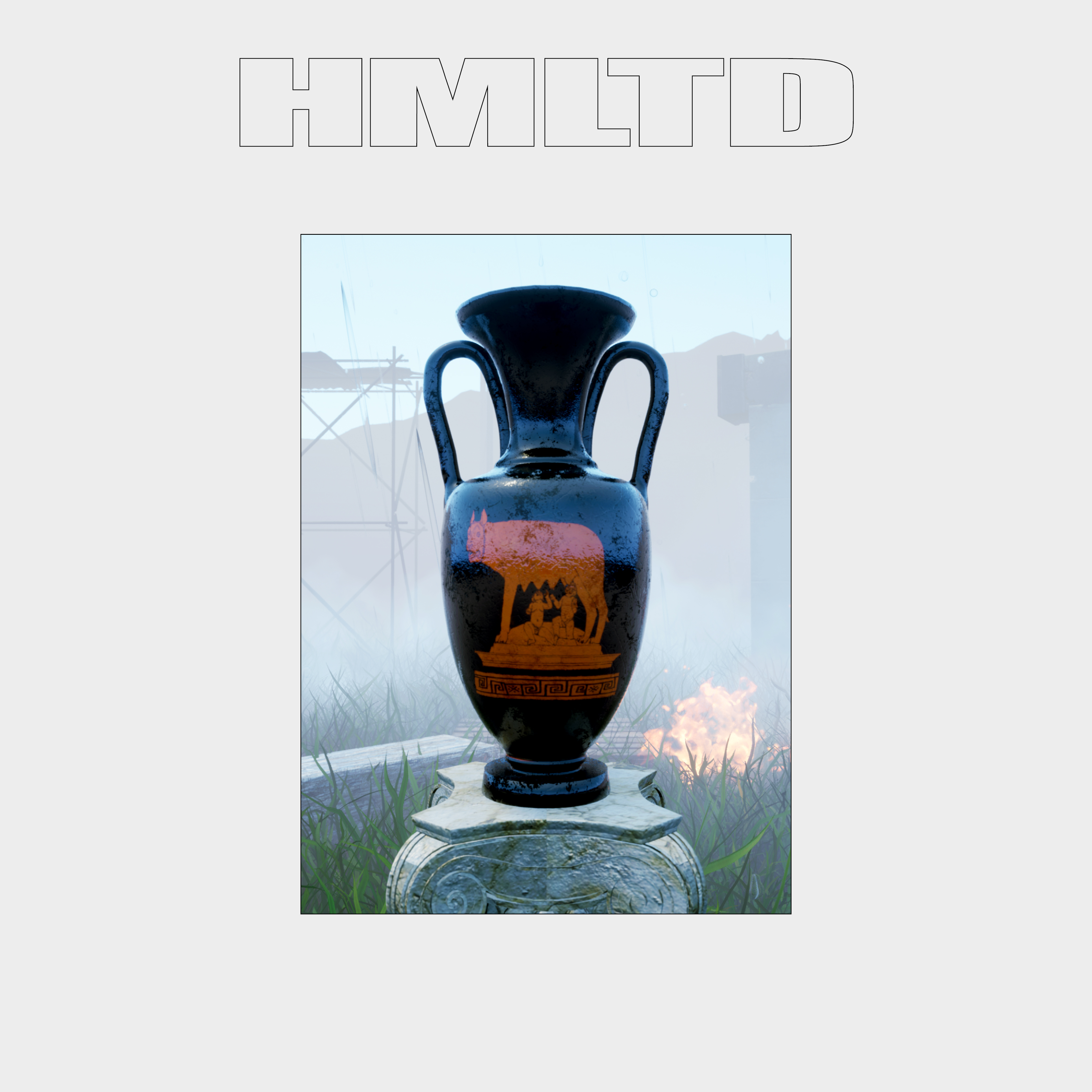

In the West, our minds are shaped by mythologies. Myths are the cultural primordial soup from which society emerges. From the story of Cain, who provides the key inspiration for our narrator; to the story of Romulus and Remus, those apparent founding fathers of Europe who appear on our album cover, and whose suckling of the starving she-wolf is surely a harbinger of capitalist exploitation in its most brutal form, our mythologies are steeped in male violence. Mythologies are powerful things, but to see a mythology for what it is, a myth, is to genealogically undermine it. This album is about the myth of man and is told as a monomyth. While we obviously must have humility about our limited role as artists, West of Eden exists to examine the myth of man and to propose a newer, better, kinder mythology. ‘The world is ours, and the world is a blank slate.’ It is a deeply personal album. Birthing it has been the single greatest pain and privilege of our lives.